"The elements of sculpture, volumes and vacuums, interrelate in a variety of ways, forming a rich and playful range of plastic positions, all of this within geometry and non-figurativism. They are present in their own nature, without realist remnants. They are ludic, since one can choose positions in one’s own way and give it any desired form. There is no need to express, represent, or symbolize. The artistic object must be pure. " [2]

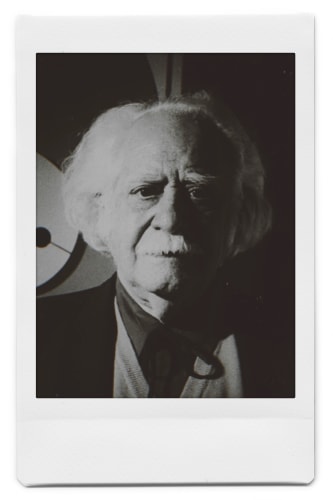

— Carmelo Arden Quin

The art of Carmelo Arden Quin is a confounding mixture of Constructivist geometry and Dada-like zeal, a heady combination that surfaces in the playful and fluid abstractions that constitute his best-known work. Fundamental to the development of his instantly recognizable aesthetic was Arden Quin’s early fascination with the teachings of the great proselytizer of “Constructive Universalism,” Joaquín Torres-García, whom he met shortly after latter’s return to Montevideo in the mid-1930s. The Uruguayan master had been in Europe, where he was co-founder of the Cercle et Carré [Circle and Square] journal alongside Michel Seuphor, and debated the possibilities of abstract art with the likes of Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg. Not only for Arden Quin, but for many artists in the Rio de la Plata, Torres-García’s role in introducing contemporary European art to Uruguay, his theory-laden radio broadcasts, and his own artwork, were groundbreaking awakenings to avant-garde practice. From Torres-García, Arden Quin took an interest in the “golden ratio”[3]—a mystical proportion used to create harmonious compositions—and was fascinated by the former’s transformable wooden “toys.” The articulated movement of these toys proved an important touchstone for Arden Quin’s later preoccupation with movement, and therefore with the ludic—or playful—as well.[4]

In 1944, Arden Quin and several others published the first and only issue of the journal Arturo, which featured manifesto-like texts and avant-garde poetry. Arden Quin’s contribution to the journal was a brief, untitled essay that outlined the pathway for a new type of art. Though emphasizing the freedom of imagination offered by Surrealism, Arden Quin argued that such an approach alone would not allow for the aesthetic progress he hoped to incite. He therefore proclaimed the necessity of a cool, scientific rationality to organize and assimilate these imaginative flights into new forms for new times. This process the artist called Invention.[5] “At best, automatism stirs the imagination,” Arden Quin wrote. “But imagination must immediately be put in check by keen artistic awareness and even cold calculations, patiently devised and applied. That will automatically lead to aesthetic creation . . . imagination, in all its contradictions, will surface; consciousness will then organize it and clear away all representative, naturalist images (even dreams) and all symbols (even the unconscious).”[6]

Among Arden Quin’s collaborators in this short-lived magazine were Tomás Maldonado, Edgar Bayley, Gyula Kosice, Torres-García, Vicente Huidobro, Lidy Prati, and Rhod Rothfuss among others. The latter’s essay interrogating and dismissing the traditional rectilinear picture plane provided a theoretical backbone for the experiments with shaped canvases embarked on by this circle of artists.[7] Arden Quin later reiterated the creative potential to be found in the non-orthogonal pictorial support in a 1945 lecture titled “The Mobile,” invoking Torres-García’s toys as well as the Italian Futurist call for dynamic painting.[8]

The mid-1940s was marked by a fracture within the loosely defined group of artists who convened around Arturo. In the coming years, two factions would spring from the journal’s collaborators—Madi (Arden Quin, Kosice, Rothfuss, and Martin Blaszko) and the Asociación Arte Concreto-Invención (Maldonado, Bayley, Enio Iommi, and Manuel Espinosa, among others). While the Madi group would not last long as a cohesive unit, their frequent issuing of proclamations and manifestos, as well as the use of exhibition models incorporating music, dancing, and poetry, has earned the group recognition as among the earliest avant-garde movements in Latin America.[9]

The Madi group officially formed in 1946 with the launch of their manifesto and the opening of their debut exhibition. The manifesto contained explicitly listed directives regarding the requirements of Madi production in each artistic medium, from Madi architecture to Madi theater. In adherence with these specifications, sculptures were to be as follows:

…three-dimensional, without color. Overall form and solid shapes with a delimited range and motion (articulation, rotation, shifting, etc.).

The requirements for painting were equally explicit:

…color and two-dimensionality. Uneven and irregular frame, flat surface, and curved or concave surface. Articulated surfaces with lineal, rotating, and changing movement.

Arden Quin’s subsequent body of work is characterized by a consistent engagement with these pre-conditions for art-making. His shaped paintings eschew any right angles in favor of the obtuse and acute, while the artist and his colleagues developed a number of innovative forms all in the name of a ludic instability: hanging mobiles; groups of movable paintings known as “coplanals”; sculptures with rearrangeable components. This especially fruitful period also saw Arden Quin’s conception of an undulating format of painting known as the “Forme Galbée.” While these paintings are stationary, their surfaces roll from concave to convex and back again in a manner conveying the sensation of motion, heightened by the optical play that occurs between the painted compositions and the undulations of the support. Arden Quin later revisited this format with new attention and vigor during the 1970s.

In 1948, following a schism within the Madi group, Arden Quin relocated to France where he would later continue to promote his strand of the movement, all the while incorporating new elements into the Madi arsenal. While Arden Quin would maintain production of irregularly shaped canvases and playful sculptures, the artist’s creativity was also fueled by his study of Georges Vantongerloo’s artwork and his bourgeoning friendship with Francis Picabia. Inspired by the former’s monochrome palette, Arden Quin likewise experimented with a reduction of his own during this period, creating what has been referred to as his “White Forms.” Reflecting on a visit to Vantongerloo’s studio, Arden Quin stated: “ . . . I hadn’t understood Mondrian, or Malevich, and even less so the Malevich of White on White. It was by observing the work of Vantongerloo that, for the first time, I was aware of that problem. Currently, with the creation of the MADI scientific movement I have blankness as an artistic basis for this new experience. For me, blank space isn’t a relationship like it is for Mondrian, nor the way emptiness is for Vantongerloo, but rather art’s essence, function, and creation.”[10]

In the mid-1950s, Arden Quin briefly returned to Buenos Aires, cofounding the Agrupación Arte Nuevo before ultimately returning to France, where, from 1958 to 1971, collage and decoupage were the artist’s medium of choice.[11] During this time, Arden Quin also dedicated himself to literary endeavors. In 1960, he cofounded with Godo Iommi a poetry group known as La Phalène, and in 1963, he inaugurated Ailleurs, a literary journal that ran until 1968. As Arden Quin’s career progressed, he incorporated new materials—plastics and metals—and maintained a strong case for the expansive possibilities of painting and sculpture until the end of his life.

The work of Carmelo Arden Quin has been included in such groundbreaking exhibitions as Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century, Plaza de Armas, Seville (Traveled to: Centre Pompidou, Paris; Josef-Haubrich Kunsthalle, Cologne; Museum of Modern Art, New York); La Escuela del Sur: El Taller Torres García y su legado, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid (Traveled to: Archer M. Huntington Art Gallery, Austin; Museo de Monterry, Mexico; Art Museum of the Americas, Washington, DC; Bronx Museum of Art, New York; Museo Rufino Tamayo, Mexico City); Arte MADI, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid (Traveled to: Museo de Arte Extremeño e Iberoamericano, Badajoz); Beyond Geometry: Experiments in Form 1940s–70s, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Traveled to: Miami Art Museum); Inverted Utopias, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; A Tale of Two Worlds, Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt (Traveled to: Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires); Sur moderno: Journeys of Abstraction, Museum of Modern Art, New York. His artwork may be found in the Daros Latin American Collection, Zurich; Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection, Caracas and New York; and the Tate Americas Foundation