“White forms . . . constructed almost as a collage, with a pictorial rather than a sculptural logic”

- Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro on Sergio de Camargo

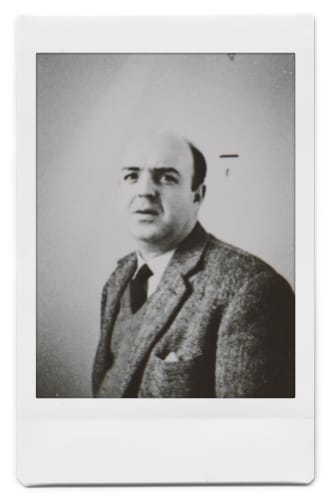

Sergio Camargo was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1930. In 1946, he began his art education under Lucio Fontana and Emilio Pettoruti at the Academia Altamira in Buenos Aries but moved to Paris in 1948 where he enrolled at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. In the French capital, he was exposed to the work of the Paris-based Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV), as well as to that of Jean Arp, Henri Laurens, and Georges Vantongerloo.[4] His most important influences in this period, however, were the philosopher Gaston Bachelard, with whom he studied at the Sorbonne, and Constantin Brancusi, whom he regularly visited. In Brancusi’s exploration of the natural world through volumetric form, Camargo found a mode of representation that captured the immaterial qualities of being that emerged from movement. In what seems to be a reference to Brancusi’s renowned sculpture series, “Bird in Space,” Camargo underscored the importance of both “bird” and “space”: “The bird in flight makes a trajectory in space. This is what really attracts me, which in spite of its immateriality is as real as the bird itself.”[5]

Camargo wished to develop Brancusi’s concerns in his own practice, bypassing representation entirely to explore the dynamic potential of volume inherent in basic geometric forms. Rather than attempting to illustrate the concrete essence of these forms “in themselves,” he was striving to present each component of his artworks as—in the words of curator and friend of the artist Guy Brett—“a sign of its possibilities.”[6]

Camargo struggled to find a way of achieving his formal aspirations until 1963, when he would accidentally discover a solution while cutting an apple. As retold by Brett:

Cutting an apple to eat it, he sliced off nearly half and then made another cut at a different angle to take a piece out. The two planes made a simple relationship between light and shadow. Camargo grasped it; unconsciously, he had made the first cylindrical element. In the apple was the synthesis he had been working towards … the combination of a single element of substance (the rounded body of the apple) and direction (the plane he had just exposed). It is a synthesis of his thought and experience in a single sculptural sign.[7]

In cutting the apple, Camargo was able to see how light acts differently based on contingent circumstances. This would be the catalyst for his first successful works—the painted wood reliefs. These monochromatic pieces follow a consistent internal logic subjected to the slightest alterations: a number of cylindrical elements are arranged across a flat plane at various angles. While there is only one module employed throughout any given piece, the variance in its length, constituent volume, and angle of projection from the picture plane produces a staggering breadth of compositional possibilities. As the natural effect of light begins to occupy the spaces between the cylinders, the interrelationship among the cylinders themselves and the quality of ambient light endows the relief with a sense of vitality, rhythm, and harmony. A Camargo is always in conversation with its surroundings, changing substantially depending on the lighting of the space it occupies. As his intellectual mentor Bachelard would frame it, light and shadow “inhabit” the work such that it can “transcend geometrical space.”[8] In other words, the presence of light and shadow allows questions of time and space to be as crucial to understanding a piece by Camargo as the forms that constitute it.

Camargo’s first breakthrough in the European art world beyond Paris would emerge from these reliefs in 1964, following a meeting with Paul Keeler and David Medalla, who offered him his first solo exhibition at Signals Gallery in London. Signals would go on to host exhibitions of Lygia Clark, Mira Schendel, and Hélio Oiticica’s work at Camargo’s behest—exhibitions that would ultimately prove critical in bringing international attention to Brazilian contemporary art.[9] Success would follow Camargo in subsequent years, with his first solo museum exhibition at the Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro in 1965, as well as his participation in the São Paulo Bienial (1965), Venice Bienniale (1966), and Documenta (1968). This success granted him access to new materials, chief among them being Carrara marble. Marble allowed Camargo to work at a much larger scale and bring his exploration of volume into a fully three-dimensional context. He also began to incorporate a wider variety of forms into his work, such as prismatic elements that would project and recede. Strong examples include his commissions for the Palácio Itamaraty, Brasília, and the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Bordeaux-Pellegrin.

Camargo left Europe and returned to Brazil in 1973. While his work for the remainder of the decade would be similar to the pieces he completed abroad, the 1980s would herald a new period for his practice. These later works are defined by a return to the cylinder, a reduction of scale, and a distillation of the antagonism between form and volume. These pieces are typically composed of two distinct elements that contradict one another in direction, volume, rigidity, or precariousness. They do not have dictated bases and can be positioned at the handler’s discretion, allowing distinct qualities to emerge from their positioning. Camargo also discovered a new material and color in this period: Belgian black marble. The material’s inherent ability to absorb light allowed Camargo to employ reflection in the same way that he would have once used shadow. Historian Paulo Venancio Filho describes this turn as a “sculptural parabola . . . in the unity of color and material, the thin matte opaque ‘hot’ white pain of the wood absorbs the light, and the hard Noir Belge extinguishes the light, a closed nucleus that merely reflects.”[10]

Camargo’s work is represented in the collections of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY; Birmingham Museum of Art, AL; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Dallas Museum of Art; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC; Kunstmuseum, Bern, Switzerland; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Museum of Modern Art, New York; and the Tate Modern, London. In 2000, the Paço Imperial, Rio de Janeiro, opened a permanent exhibition space for the artist, which includes a replica of his art studio in Jacarepaguá, Brazil. Camargo’s work has been the subject of major retrospectives at the Museu de Arte Moderna, Rio de Janeiro, in 1993; the Stedeljik Museum, Schiedam, in 1994; and the Instituto de Arte Contemporânea, São Paulo, in 2010, which traveled to the Museu Oscar Niemeyer, Curitiba, Brazil, in 2012.