"I had difficulties with the muralists, to the point that they accused me of being a traitor to my country for not following their ways of thinking. But my only commitment is to painting. That doesn't mean I don't have personal political positions. But those positions aren't reflected in my work. My work is painting.”[3]

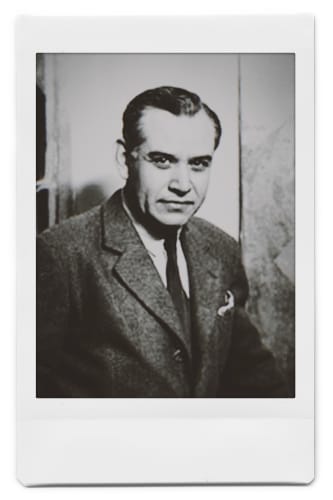

- Rufino Tamayo

Widely regarded as one of the most important painters from Mexico, Rufino Tamayo came of age in his native country’s post-revolutionary context. At a time when “the big three”—Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros—were cultivating a realistic aesthetic saturated in leftist politics, Tamayo questioned their representation of Mexican identity and its founding myths. Wary of the insularity of their approach that shunned modern art as elitist and anti-proletariat, Tamayo remained open to larger art world trends and aspired to a universal artistic language.[2] While the muralists painted frescoes across the country and the United States, Tamayo, though himself an accomplished muralist, embraced the easel in the face of much condemnation. Reflecting on this time in 1981, Tamayo remembered, “I had difficulties with the muralists, to the point that they accused me of being a traitor to my country for not following their ways of thinking. But my only commitment is to painting. That doesn't mean I don't have personal political positions. But those positions aren't reflected in my work. My work is painting.”[3]

Tamayo received formal artistic training as a student at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, where he enrolled in 1917 before starting work at the Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Historia y Etnografía in 1921. Working closely with the institution’s pre-Columbian objects as well as examples of Mexican popular art,[4] the position was of profound importance for the artist’s future aesthetic. Reflecting on his time at the museum, Tamayo stated: “It opened my eyes, putting me in touch with both pre-Columbian and popular arts. I immediately discovered the sources of my work—our tradition.”[5]

In 1926, Tamayo made his first trip to New York. Initially settling on 14th street—where his neighbors included the artists Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Stuart Davis, Marcel Duchamp, and Reginal Marsh—Tamayo saw for the first time the works of modern European masters in person.[6] During his time in the city, Tamayo was introduced to Carl Zigrosser of the Weyhe Gallery, where he would hold a solo exhibition followed by a second at the Art Center in 1927 before returning to Mexico in 1928. Here, he served as the head of visual arts in the Ministry of Public Education and taught painting in various capacities before returning to New York in 1936. Of crucial importance in Tamayo’s aesthetic development was the Valentine Gallery’s presentation of Pablo Picasso’s 1937 masterwork Guernica. On view at the gallery in 1939, and again at the Museum of Modern Art later that year, its fragmented creatures besieged by violence would have a significant impact on Tamayo, whose own compositions would take on existential and cosmic textures in the coming decade.[7] Indeed, from 1946 to 1956, his paintings were characterized by figures inspired by Jean Dubuffet, staged in dramatic confrontation with their surroundings. Whether basking in the cosmos, or under threat of attack by mechanisms of war or unchecked technological progress, Tamayo’s lonely figures speak to the existential anxieties of the WWII context and its aftermath.[8]

Living in New York—where he spent his winters while summering in Mexico City—Tamayo presented his art in now-legendary venues such as the Julien Levy Gallery, Valentine Gallery, and Pierre Matisse Gallery, as well as several iterations of the Whitney Museum’s “Annual” exhibition. Tamayo also worked as a teacher at the prestigious Dalton School—where one of his most famous pupils was Helen Frankenthaler—and later taught at the Brooklyn Museum. Solo exhibitions of his work were held at the Arts Club of Chicago, Cincinnati Art Museum, and the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, while group shows included Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Tamayo settled in Paris in 1949, where his reputation as a painter continued to grow as his compositions would eventually become sparser in detail. During a 1951 interview, Tamayo explained: “Right now, I’m pursuing greater simplicity. My figures must be transformed into a mere nucleus. I shall eliminate more and more . . . who knows, the figures in my next paintings may have neither mouths nor eyes.”[9] Tamayo featured in the 1950 Venice Biennial, and shared the First International Painting Prize at the 1953 São Paulo Biennial. His work was shown internationally in numerous exhibitions, and the decade of the 1950s saw the completion of several murals, including at the Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City; Dallas Museum of Fine Arts; and the University of Puerto Rico. In 1958, Tamayo created a mural for the UNESCO Headquarters titled Prometheus Bringing Fire to Mankind. Subsequent mural commissions include the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City (1964) and the Mexican Pavilion at Expo ’67 Montreal.

In the early 1960s, Tamayo moved to Mexico permanently, where he would live and work for the rest of his career, creating compositions renowned for their colors and textures. During this decade, he held retrospectives at the Museo de Art Moderno, Mexico City; Palacio de Bellas Artes; Phoenix Museum of Fine Arts; and was honored as a special guest at the 1968 Venice Biennial. Having begun acquiring pre-Columbian art in 1951, Tamayo donated his collection to Oaxaca in the form of the Museo de Arte Prehispánico de México Rufino Tamayo, which opened its doors in 1974. It would be the first of two institutions Tamayo helped found, the second being the Museo Rufino Tamayo in Mexico City, which houses the artist’s collection of international contemporary art. In 1977, Tamayo was named “Dean of Latin American Painting” during the 1977 São Paulo Biennial, which accompanied a massive exhibition of his work at the fair.[10] Two years later, in 1979, an extensive retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum would bring together over 100 of his own artworks into conversation with approximately 150 artifacts from Mexico.[11] Tamayo’s work continues to attract scholarly attention today, with recent exhibitions including Tamayo: The New York Years at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and Rufino Tamayo: Innovation and Experimentation, organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Examples of Tamayo’s groundbreaking paintings are found in the collections of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY; Art Institute of Chicago; British Museum, London; Brooklyn Museum; Cleveland Museum of Art; Dallas Museum of Art; Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Philadelphia Museum of Art; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Tate Galleries, London; and the Vatican Museums.